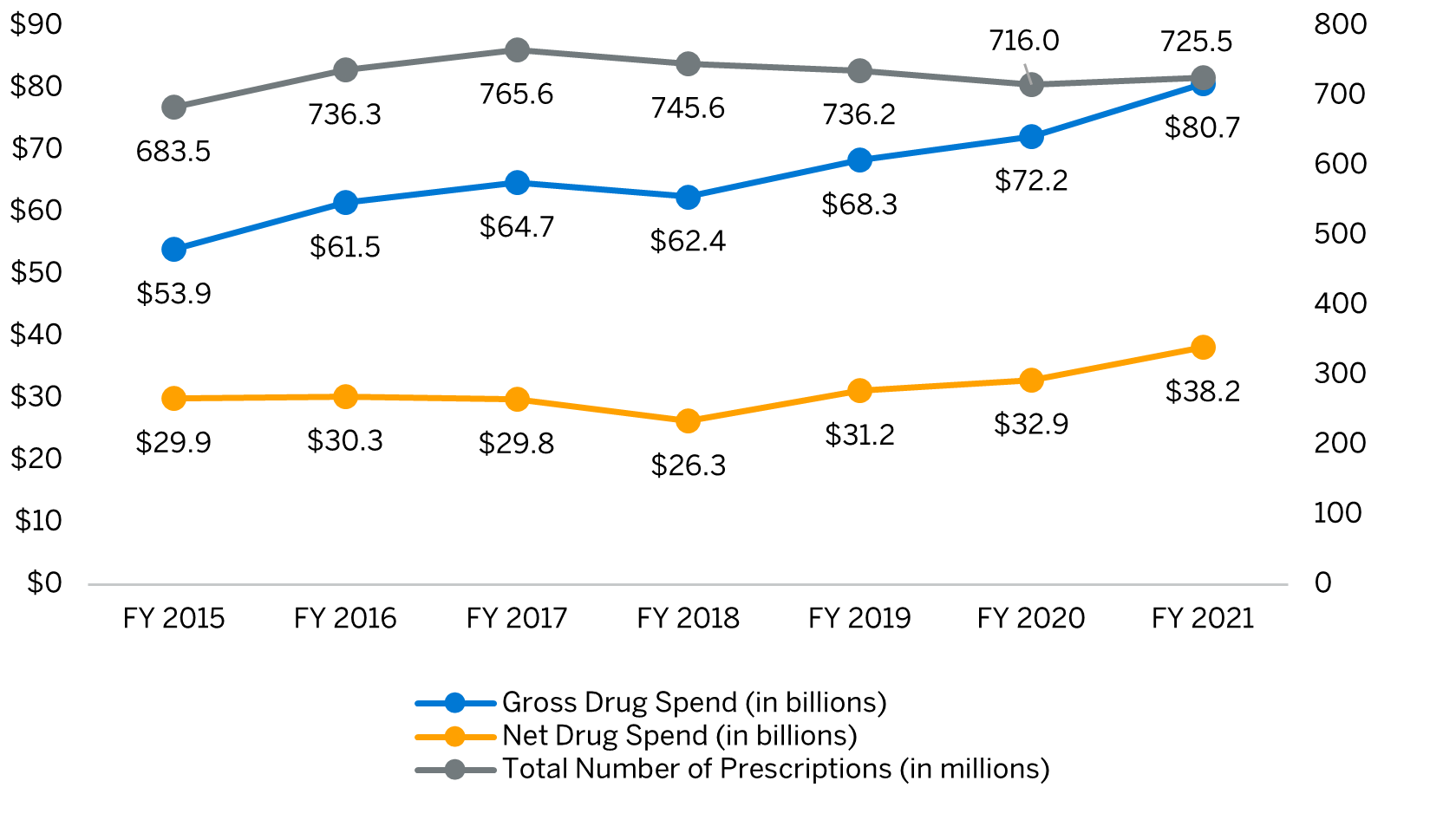

Medicaid outpatient prescription drug net spend has increased from $29.9 billion in federal fiscal year (FY) 2015 to $38.2 billion in FY 2021, an average annual growth of more than 4%, according to Milliman’s analysis of State Drug Utilization Data and State Budget & Expenditure Reporting data.1,2,3 The outpatient drug expenditure is expected to continue to increase with more specialty drugs, molecularly targeted oncology drugs, and cell and gene therapy approvals on the horizon.4

Trend in number and spend for Medicaid outpatient prescription drugs, FY 2015 – FY 2021

Abbreviation: FY = Federal fiscal year.

Source: Milliman analysis of 2014-2021 State Drug Utilization Data (SDUD), State Budget & Expenditure Reporting data, and MACStats: Medicaid and CHIP Data Book.

Note: Gross to net cost difference is driven by Medicaid Drug Rebate Program and state supplemental rebates, and excludes Managed Care Organization supplemental rebates. SDUD includes drugs used in the hospital outpatient setting. SDUD excludes 340B claims and removes data that is less than eleven (11) counts.

In FY 2021, the Medicaid outpatient prescription drug gross-to-net difference of $42.5 billion was primarily driven by manufacturer drug rebates.1,2 In order for a drug to be covered by Medicaid, the manufacturer must enter into a National Drug Rebate Agreement with the Department of Health and Human Services via the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP).5 While these statutorily required federal rebates have the greatest contribution in lowering gross drug spend, States, and in some instances Managed Care Organizations (MCOs), may enter into supplemental drug rebate agreements with manufacturers to access additional rebates.

While manufacturer rebates help offset the expense of covered outpatient drugs, state Medicaid programs may implement a variety of clinical programs, claims edits, and utilization management strategies to manage the pharmacy benefit in a cost-effective, clinically appropriate manner. Several key strategies are described below.

- Prior authorization (PA): Pre-approval requirement for prescribing a particular drug to ensure cost-effective, clinical appropriateness.

- Quantity limit (QL): Limitation to the quantity of drug dispensed per prescription or within a specified period of time.

- Step therapy (ST): Trial of other drug(s) before coverage is provided for a specific drug.

- State-mandated Preferred Drug Lists (PDL): A drug list to maximize rebates and drive utilization toward the lowest net cost options via “preferred” and “non-preferred” designations. An upcoming white paper will discuss PDLs in detail.

- Drug utilization review (DUR): Medicaid programs are required to have a structured ongoing program to review prescribing patterns and drug utilization. Some examples include:

- Clinical edits: Claim review process to verify appropriate submission, such as gender and age, that aligns with FDA-approved or medically accepted indication.

- Safety edits: Intended to promote safe and effective use of medications, such as drug-drug or drug-disease interaction, and duration limits.

- Appropriate use: Verify that the dispensed drug has supporting medical diagnoses to ensure appropriate use of a drug at risk for misuse and/or abuse.

- Clinical programs: Provided by healthcare professionals to target specific populations and/or disease states to improve patient outcomes. Some examples include Disease Management (e.g., diabetes, hemophilia), Recipient Restriction (i.e., pharmacy lock-in), prenatal/maternal health, etc.

- Medical pharmacy management: Managing prescription drugs that are covered under the medical benefit. This could involve utilization management, site-of-care optimization, medical and pharmacy benefit duplicative claims review, etc.

- National Drug Code (NDC) exclusion: Excludes coverage for specific NDCs where it does not meet the definition of a covered outpatient drug or is a drug that is excluded from coverage (e.g., used for fertility, cosmetic purposes, etc.) as described in Section 1927 of the Social Security Act.

- Prescription limits: Limits the number of prescriptions a patient may fill per month. Certain classes of drugs such as antiepileptics may be excluded from such limits.

- Over-the-counter (OTC) product coverage: Select OTC products may be covered on the PDL when prescribed by a licensed prescriber to encourage use before higher-cost prescription drugs.

- Patient cost-share: Nominal patient cost-share for select drugs to reduce prescription drug stockpiling. This may be statutorily restricted in certain states.

The focus of these strategies is to maximize pharmacy savings while optimizing health outcomes and access to appropriate level of care. For example, PDL, PA, and ST are used to encourage use of preferred products with comparable clinical indications and lower net costs to States, whereas QLs and prescription limits are used to prevent inappropriate utilization. By influencing prescribing and utilization patterns, these tools can work in harmony to lower the overall healthcare cost to States.

Appropriate application of the aforementioned strategies may improve prescribing behaviors, leading to an overall decrease in medical cost. Upfront investment (e.g., human capital, vendor contracting) may be required to implement these strategies. However, effective management can lead to significant downstream savings. For example, prenatal/maternal health programs can identify high-risk pregnant members through pharmacy claims review for medications treating high blood pressure, diabetes, etc., as well as identify controlled substance use. Early identification of and intervention in such members can reduce maternal mortality and Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) rates and provide medical cost offset. An upcoming paper will discuss clinical gaps and opportunities for States to consider in detail.

Understanding MCOs’ capabilities and maintaining oversight, specifically with multiple MCO presence, may provide States with realistic benchmarks. For example, a State can benchmark MCOs to maximize level of management, clinical outcomes, and spend in specific populations between programs. Oversight may also provide States with the opportunity to streamline efforts between MCOs, increase efficiency, and improve provider and member satisfaction.

Efficiencies are much needed in the medical drug management space, as many of the new specialty drugs with high list prices are covered through the medical benefit. Claims submission delays, complexities, and variances in provider billing and reimbursement all pose significant challenges in attaining a clear picture of the medical drug spend and utilization. A coherent management strategy that is consistent across the pharmacy and medical benefits can help avoid duplicate therapies and double billing, and also limit waste. Some strategies to manage medical drug spend include but are not limited to Site-of-Care management, HCPCS quantity limit, and white/brown-bagging initiatives (i.e., drug is dispensed through a pharmacy and delivered to the provider to administer).

Collaborative management with MCO stakeholders can result in competitive pricing responsive to the dynamic pharmacy landscape and result in better health outcomes.

Upcoming papers will provide in-depth discussions of opportunities for States to manage pharmacy and medical drug expenditures.

1State Drug Utilization Data. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Accessed January 18, 2023. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/prescription-drugs/state-drug-utilization-data/index.html

2State Drug Utilization Data. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Accessed January 18, 2023. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/prescription-drugs/state-drug-utilization-data/index.html

3Medicaid Drug Spending Trends. MACPAC. Accessed January 18, 2023. https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Medicaid-Drug-Spending-Trends.pdf

4Williams E. Medicaid Outpatient Prescription Drug Trends During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Kaiser Family Foundation. Accessed on January 27, 2023. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-outpatient-prescription-drug-trends-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/

5Medicaid Drug Rebate Program. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Accessed January 4, 2023. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/prescription-drugs/medicaid-drug-rebate-program/index.html

6Payment for Covered Outpatient Drugs. Social Security Administration. Accessed January 4, 2023. https://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/ssact/title19/1927.htm